Long time no post – the idea was to spend time taking photos during spring and summer and enjoy the underwater world vicariously by blogging in autumn and winter. However, something terrible happened on my only dive of 2025: my underwater housing sprung a leak! The housing was not flooded to an extent that it damaged my camera but it needed to be repaired before I could get back underwater. Unfortunately there is only one place that can do that, backscatter all the way in California, and even more unfortunately, U.S. customs decided to keep my package on a shelf for over a month. I have never seen an octopus in my decade of diving but of course people reported eight or so per dive last month so I was feeling very sorry for myself!* Anyway, I have been confined to the shoreline so far. To cope with that, I bought a weird chinese macro-wide angle lens to play with which I will post about later. I also used my ‘normal’ 60mm macro lens (sometimes with a Raynox lens attached to the front for extra magnification) and took some time to focus on periwinkles.

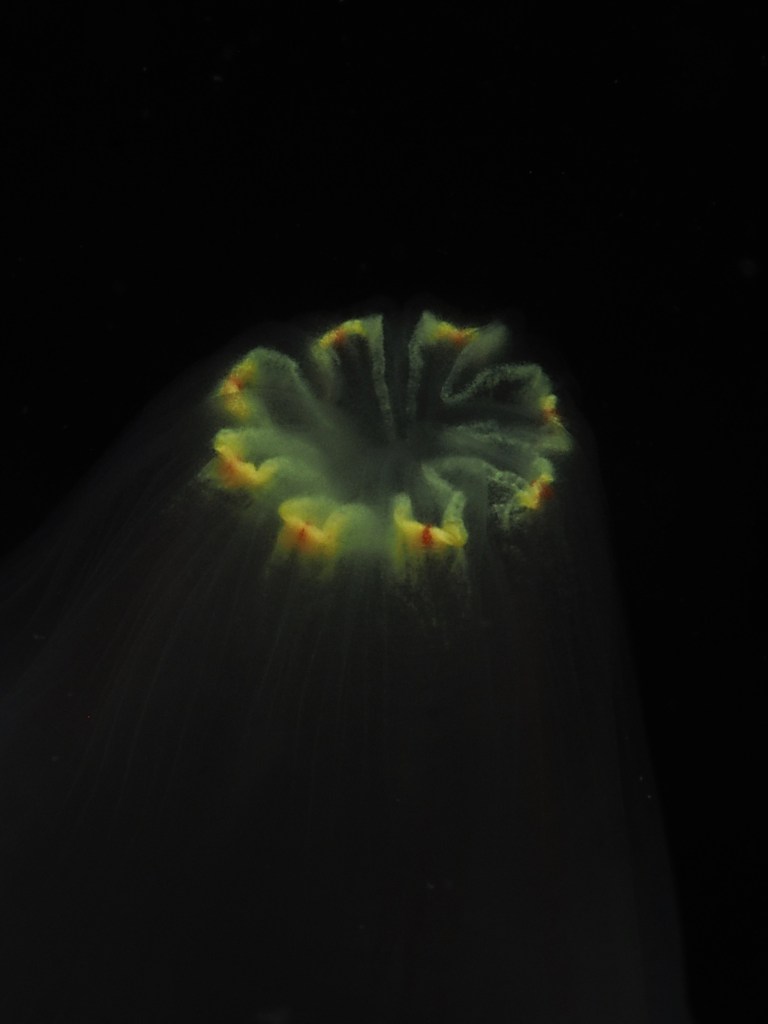

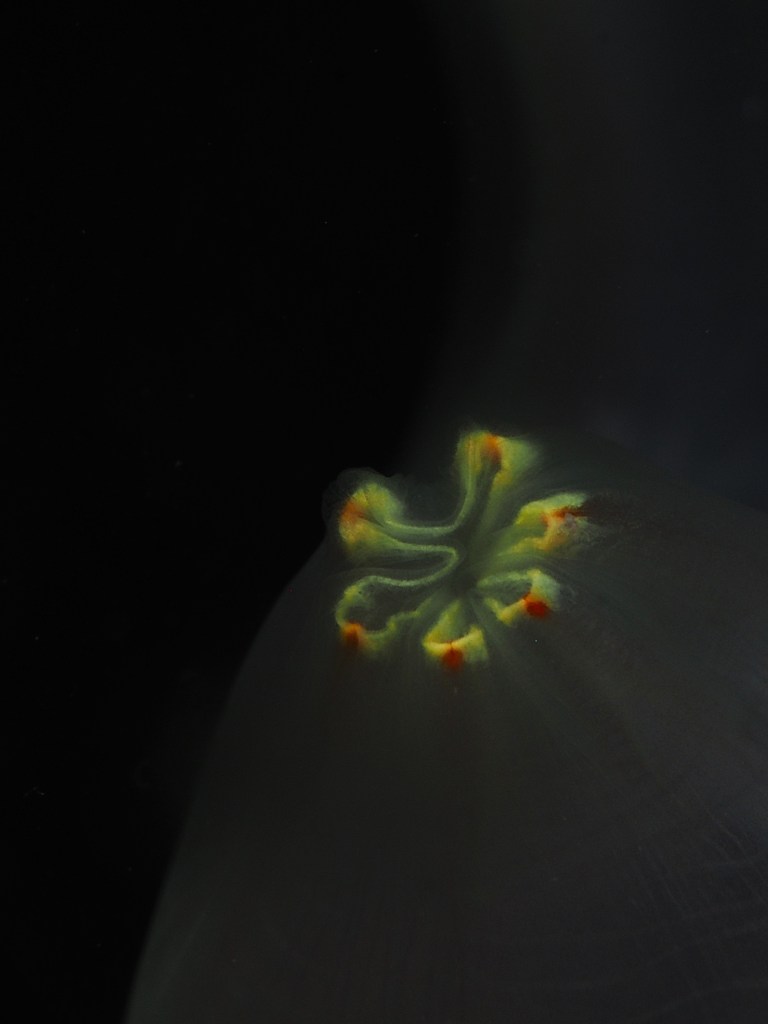

At the top and below a Flat Periwinkle (Littorina obtusata or maybe L. fabialis – distinguishing is very hard as it requires investigating differences in penis shape!). As you can see the locations are not always glamorous, but if you zoom in you can still find beauty!

Flat periwinkles tend to be most active above-water, followed by the smaller Rough Periwinkle (Littorina saxatilis – below) with the Common Periwinkle (Littorina littorea – below that) only occasionally moving about.

Finally, a tiny species the Small Periwinkle (Littorina Melharaphe neritoides). Probably overlooked by most, as it is tiny (up to 8mm, usually smaller) and hidden between barnacles (or even nestled in empty barnacle cases) high on the shore.

* and no, I could not bring myself to go diving without a camera…